Another era of quantitative tightening beckons

March 2022

Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria may have devastated parts of the US in 2017 but the Janet Yellen-led Federal Reserve was determined to persist with an unprecedented way to tighten monetary policy. The central bank in October that year commenced selling the assets on its balance sheet, to unwind eight years of on-and-off quantitative easing.[1]

The ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013 showcased the risks. In that year, comments from the Ben Bernanke-led Fed that it would reduce its monthly asset purchases sparked financial turbulence. Such turbulence, the Fed backtracked. No tapering worthy of the name occurred and by 2015 another round of quantitative easing was underway.[2]

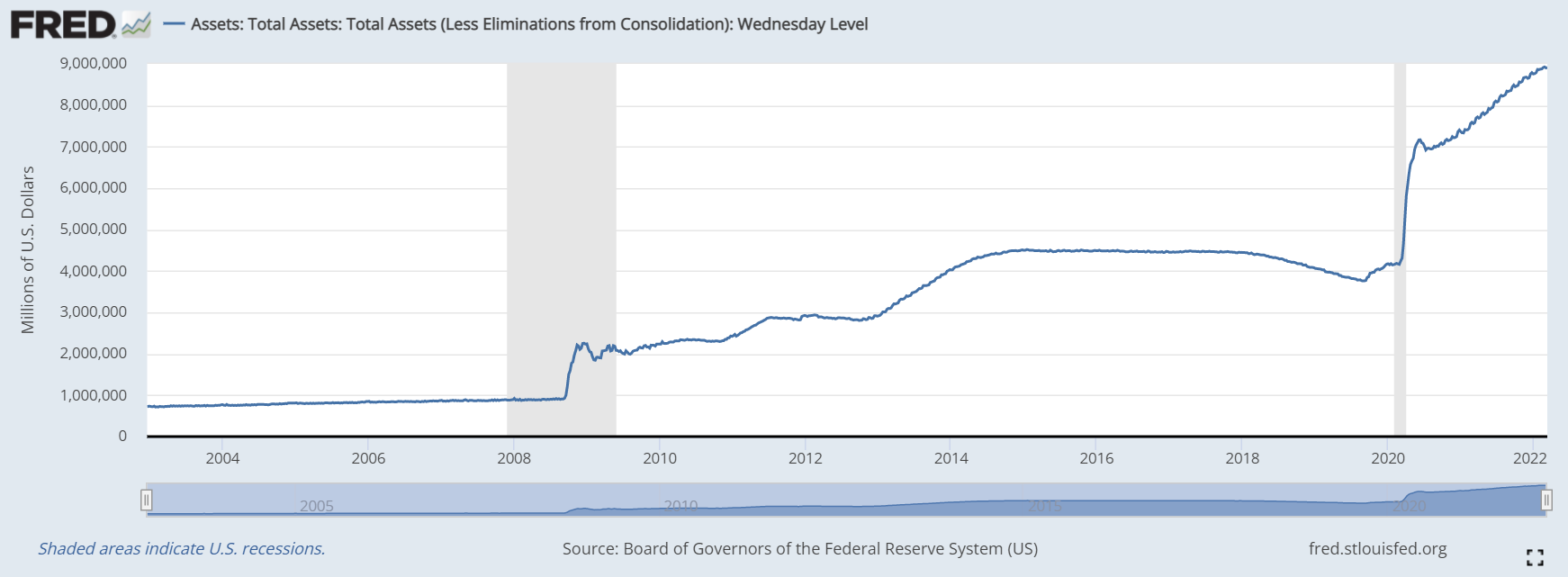

Investors were thus wary of the quantitative tightening of 2017. What would happen when the Fed shrank a balance sheet that had swelled to US$4.4 trillion from US$900 billion in 2008? How would investors react when the Fed refrained from reinvesting as much as US$50 billion in bonds that matured every month, even if it was the most conversative approach to shrinking a balance sheet?[3] Some turbulence eventuated. But the ‘balance sheet normalisation’ went smoothly enough for a Fed led by Jerome Powell from February 2018. Until it didn’t.

On 16 September 2019, when the Fed balance sheet had contracted by about US$600 billion to US$3.8 trillion, strains in the repo market spilled into the money market and the secured overnight financing rate jumped from 2.43% to above 5%, an event the Fed described as “surprising”. To provide enough liquidity to ensure short-term interest rates behaved, the Fed restarted asset purchases.[4]

Investors nowadays might keep this episode in mind when the Fed restarts asset sales accompanied by at least one other major central bank. On January 26 this year, Powell announced the Fed would “in a predictable manner”[5] reduce its balance sheet that has swelled by US$4.5 trillion since the pandemic struck to US$8.9 trillion now.[6] Eight days afterwards, the Bank of England announced it would reduce “in a gradual and predictable manner” the 895 billion pounds worth of debt it has purchased since 2009.[7]

To understand what might happen when the biggest buyers of debt become the biggest sellers, it helps to revisit what happens when central banks undertake quantitative easing. Under the non-conventional policy invented by the Bank of Japan in 2001, a central bank creates money (electronically) as an asset on its balance sheet and buys financial securities in the secondary market with interest-paying reserves. The purpose is to reduce long-term interest rates.[8] Quantitative tightening, as the name suggests, is the reverse process.[9] Once central banks ‘destroy’ money, long-term interest rates should be higher than otherwise.

The first question to ask is: Why do central banks need to reduce their balance sheets? A valid answer is they have no need to. The bloated balance sheets are not causing financial instability, even if pumping them up came with side effects such as asset inflation and excessive risk-taking and is a culprit behind consumer inflation.

But central banks are intent on shrinking their balance sheets. (The Bank of England in February started monthly sales of 20 billion pounds worth of corporate bonds.) Why? The main reason is that central bankers are worried that an overstuffed balance sheet could shake the financial system. At some level, the public might lose confidence in the value of their fiat money. Central banks fret that, if circumstances were to change, the market-based rate of interest they pay the holders of their reserves might not be attractive enough to stop these sums being lent out and inflation might accelerate. They worry too the policy option is, in Powell’s words, “habit forming”.[10]

Powell, by this comment in 2012 when as a member of the policy-setting board he opposed Fed asset buying, meant it’s another ‘Fed put’. This is slang for the moral hazard whereby investors take more risk because they are confident the Fed, in a quest to protect the economy, will act to cut their losses.

Another reason for quantitative tightening is political. Quantitative easing stirs charges that central banks make it easier and cheaper for governments to run fiscal deficits. Reversing the process would depower those accusations and reassert central-bank independence.

One motivation for the Bank of England for selling assets appears to be that higher short-term interest rates could turn central bank profits into losses for government budgets.[11] If short-term rates rise enough, the interest central banks pay on their liabilities on their balance sheets will exceed the interest they earn on their assets. The bigger the balance sheet the bigger the losses.[12] It means too that a large balance sheet could restrict how high the Bank of England and others could raise key rates. The Fed would be aware of the political storm created if it were to become a loss-maker for Washington.[13]

It’s notable that the Fed and Bank of England talk of undertaking quantitative tightening in a “predictable manner”. That’s probably because so much surrounding the stance is unknown. No central bank has ever reversed its asset buying over the medium to long term.[14]

The danger today is that central banks want to shrivel their balance sheets when they are raising their key rates to combat inflation. Whereas in 2018-2019, inflation was tame, the Fed now must contend with inflation at 7.9% in the 12 months to February, the highest since 1982. The Bank of England must suppress inflation at 5.5% over the 12 months to January, the highest in three decades. No one knows how high bond yields might rise as central banks raise their key rates and shrink balance sheets, especially if inflation accelerates further.[15] Nor does anyone know how high bond yields could rise without triggering the financial mayhem that occurs when investors anticipate a recession.

But the bigger menace of quantitative tightening is that it might show the Fed is not serious about curbing the inflation it dismissed as “transitory” throughout 2021. Even though all US inflation gauges have exceeded Fed comfort levels for months, the Fed is buying assets until the end of March. A Fed that couldn’t immediately end asset purchases when inflation first reached 5% mid-last year (for the 12 months to May) is unlikely to allow asset sales to destabilise markets.[16] It’s likely that come trouble the Fed would cease asset sales or even resume asset buying – aka QT1. With the cash rate close to zero, quantitative easing is the best Fed put around. Don’t be surprised if it resumes.

To be sure, the pressure is mounting on the Fed to control inflation, especially as energy and food prices soar after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But adjusting the key rate will be the means to curb price rises, not asset sales. A Fed balance sheet at double the size of 2018-2019 must be riskier to puncture without mishap – so even timid asset selling could stir trouble. The risks would increase if the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank were to join the Bank of England and the Fed in shrinking their balance sheets. An inflation outbreak that required an abrupt tightening of monetary policy could escalate the risks of doing nothing about a swollen balance sheet. A recession that prompted more quantitative easing might make it harder to envisage that central banks would ever reduce their balance sheets to pre-2008 levels.

Amid the uncertainty, best to frame the Fed’s balance sheet as a tool to ensure today’s asset bubbles don’t burst. The longer-term problem, of course, is that one day the Fed put will be kaput. Investors might confront a hurricane.

The kaput put

On 19 October 1987, the US share market dropped on opening by about 10%, to follow a 5% decline the previous Friday. Fed chief Alan Greenspan convened a meeting of the Fed’s policy-setting board. No action was proposed though one board member urged Greenspan not to fly from Washington to Dallas that day to give a speech.[17]

But travel Greenspan did. On arrival in the Texas city, he asked a Dallas Fed official who greeted him at the airport how the stock market had gone. “It was down five zero eight,” came the answer. Greenspan felt vindicated in travelling, given the stock market had lost only 5.08 points. “What a terrific rally,” Greenspan said.

But the man from the Dallas Fed looked pained. Greenspan realised the man meant the Dow Jones Industrial Average had plunged 508 points, nearly 25% of its value and the largest single-day loss in history.

Amid concerns the Chicago Mercantile Exchange could collapse due to the events of ‘Black Monday’, Greenspan ensured the Fed on the Tuesday issued a one-line statement. It said the central bank reaffirmed “its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system”. In the first hour of trading, the Dow recouped 40% of the previous day’s losses. The ‘Greenspan’ put was born (as was Greenspan’s reputation as ‘the maestro’).

The Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen/Powell put has lived a healthy life since. The Fed put has generally manifested itself as rate reductions. But it takes the form of emergency liquidity facilities. It comes in soothing comments (though none as effective as Mario Draghi’s ‘whatever it takes’ of 2011 even if the Greenspan “irrational exuberance” comment of 1996 was a prescient warning).[18] And the put takes the form of quantitative easing.

Fed leaders have acted to support asset prices because falling markets can destablilise the financial system and hurt the economy. Declines in asset prices can make consumers feel poorer and can batter their confidence, and thereby restrict the consumer spending that drives about 70% of the economy.

The biggest risk with the Fed put is that it cultivates asset bubbles. In 1959 when Greenspan was under the influence of philosopher Ayn Rand, he presented a paper that argued bubbles were recognisable even when investors were irrational. Investors who bid risk premiums close to nothing have taken leave of their senses because they were forgetting the limits “of what can be known about future economic relationships,” he said.[19] In his PhD thesis of 1977, Greenspan warned how rising incomes and rising financial prices fed into each other to create asset bubbles that would eventually burst, a contrary view in the heyday of efficient-market belief.[20] Yet as Fed chief from 1987 to 2006, Greenspan acted to ensure bubbles never burst.

Greenspan biographer Sebastian Mallaby encapsulated this doublethink in his book title: The man who knew. Mallaby argues that Greenspan knowingly acted carelessly as Fed chair – usually under the cover of aiming for full employment – because “he calculated that acting forcefully against bubbles would lead only to frustration and hostile political scrutiny”.[21]

The political pressures are unlikely to have changed. The biggest flaw surrounding the Fed put is that it’s only credible if a central bank can muster up some sound action. The danger is that one day the Fed might run out of credible emergency measures.[22] A US cash rate close to 0% means rate cuts are no recourse. (The Fed is against a negative key rate.) At some point, a swollen Fed balance sheet might hobble the Fed’s ability to inject money into the economy. It’s likely the dangers and higher interest rates stemming from quantitative tightening will prevent the Fed shrinking the balance sheet so much quantitative easing can safely restart to prop up asset bubbles.

Come the day when the Fed is powerless to respond to bursting asset bubbles, maybe the storms that tear through financial markets can be called Hurricanes Alan, Ben, Janet and Jerome.

By Michael Collins, Investment Specialist

The Fed’s expanding balance sheet

Federal Reserve of St Louis. FRED economic data. Shaded areas signify recessions.

Source: fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL

[1] Federal Reserve. ‘Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement.’ 20 September 2017. federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20170920a.htm

[2] The Fed reassured investors everything was ‘data dependent’. See Reuters. ‘Key events for the Fed in 2013: the year of the ‘taper tantrum’. 12 January 2019. reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-2013-timeline-idUSKCN1P52A8

[3] The quantitative tightening ended as the Fed cut its key rate three times in four months in 2019 to help a slowing US economy extend its longest growth spree (before slashing the key rate when the pandemic struck in 2020).

[4] The central bank later blamed its asset-selling coinciding with corporate tax payments and bond sales by the US Treasury for the troubles. Federal Reserve notes. ‘What happened in money markets in September 2019?’ 27 February 2020. federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/what-happened-in-money-markets-in-september-2019-20200227.htm

[5] Federal Reserve. ‘Transcript of Chair Powell’s press conference January 26, 2022.’ Page 4. federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20220126.pdf

[6] Federal Reserve of St Louis. FRED economic data. Chart. ‘Assets: Total assets (less eliminations from consolidation): Wednesday Level (WALCL). fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL

[7] The Bank of England will do this by refraining from reinvesting government debt that matures, immediately selling 20 billion pounds of corporate debt and, when the key rate reaches 1%, by selling gilts. Bank of England. ‘Bank rate increased to 0.5% – February 2022.’ 3 February 2022. bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-summary-and-minutes/2022/february-2022

[8] In its purest form, quantitative easing is an action wholly within monetary policy. Quantitative easing can veer towards money printing – an action that falls under fiscal policy – if it is used to finance government deficits, as has been doing the Bank of England.

[9] Bloomberg News. QuickTake. ‘How do central banks shrink their balance sheets?: QuickTake Q&A.’ 23 June 2017. bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-23/how-do-central-banks-shrink-their-balance-sheets-quicktake-q-a

[10] ‘Powell backed Fed’s bond-buying plan with reservations in 2012.’ The Wall St Journal. 5 January 2018. wsj.com/articles/powell-backed-feds-bond-buying-plan-with-reservations-in-2012-1515171836

[11] Jeremy Warner. ‘The £100bn QE timebomb about to hit Britain’s struggling finances.’ The Telegraph of the UK. 12 February 2022. telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/02/12/100bn-qe-timebomb-hit-britains-struggling-finances/

[12] The Federal Reserve’s profits were worth US$107.4 billion to the US federal budget in fiscal 2021. The US cash rate might need to climb above 2.5% to turn central-bank profits into losses. No one is expecting that, particularly as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine saps economic growth. See Bloomberg News. ‘US Treasury’s golden Fed goose is about to get cooked.’ 17 February 2022. bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-02-17/the-federal-reserve-s-impending-profit-squeeze

[13] The Fed would recall that populists against its independence twisted its decision in 2011 to pay interest on bank reserves into allegations the Fed was gifting banks billions of taxpayer dollars for not lending.

[14] House of Lords. Economic Affairs Committee. First report of sessions 2021-22. ‘Quantitative Easing – a dangerous addiction?’ 16 July 2021. Page 52. publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5802/ldselect/ldeconaf/42/42.pdf

[15] The Bank of England in January and February has increased its key rate by 25 basis points, to lift it to 1%. The Fed is poised to raise its key rate in March.

[16] See Mohamed El-Erian. ‘The Fed’s historic error.’ Project Syndicate. 28 February 2022. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/us-federal-reserve-inflation-policy-mistakes-by-mohamed-a-el-erian-2022-02

[17] Sebastian Mallaby. ‘The man who knew. The life & times of Alan Greenspan.’ Chapter 16 Light Black Monday. Pages 340 to 355. Bloomsbury. 2016

[18] Federal Reserve. ‘Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan.’ At the annual dinner and Francis Boyer lecture of The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, DC. 5 December 1996. federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/1996/19961205.htm

[19] Mallaby. Op cit. Pages 56 to 57.

[20] Mallaby. Op cit. Pages 212 to 213.

[21] Sebastian Mallaby. ‘The doubts of Alan Greenspan.’ The Wall Street Journal. 29 September 2016. wsj.com/articles/the-doubts-of-alan-greenspan-1475167726

[22] Another risk is the Fed pushes too hard on quantitative easing by buying a wider array of securities. Over the pandemic, the Fed bought corporate debt while the Bank of Japan purchased equities. Such actions would support asset prices to a point where it doesn’t and the damage would be even larger.

Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 (‘Magellan’) and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should obtain and consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement (‘PDS’) and Target Market Determination (‘TMD’) and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making a decision about whether to acquire, or continue to hold, the relevant financial product. A copy of the relevant PDS and TMD relating to a Magellan financial product may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au.

Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any financial product or service, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to implement its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain ‘forward-looking statements’. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements.

This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. No representation or warranty is made with respect to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information contained in this material. Magellan will not be responsible or liable for any losses arising from your use or reliance upon any part of the information contained in this material.

Any third party trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and Magellan claims no ownership in, nor any affiliation with, such trademarks. Any third party trademarks that appear in this material are used for information purposes and only to identify the company names or brands of their respective owners. No affiliation, sponsorship or endorsement should be inferred from the use of these trademarks. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan.